Published: September 19, 2004

Article originally published at http://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/19/politics/campaign/19state.html

T. CHARLES, Mo. - Tom Ampleman, a blue-collar union member who lives near this suburb just outside St. Louis, says he voted for Bill Clinton twice and then Al Gore, but he is now grappling with deep religious misgivings about the Democratic Party.

T. CHARLES, Mo. - Tom Ampleman, a blue-collar union member who lives near this suburb just outside St. Louis, says he voted for Bill Clinton twice and then Al Gore, but he is now grappling with deep religious misgivings about the Democratic Party.

"I haven't declared myself a Republican, but if I had to go in there and vote right now I probably would vote for the Republicans," Mr. Ampleman said recently, sitting in his pickup truck at a public park here.

"I'm not happy with the moral issues at all with the Democrats," continued Mr. Ampleman, who works as a welder at an aerospace company. "The Republicans will hurt me in the long run in providing for my family, but it's probably more important to watch out for the unborn and that kind of stuff."

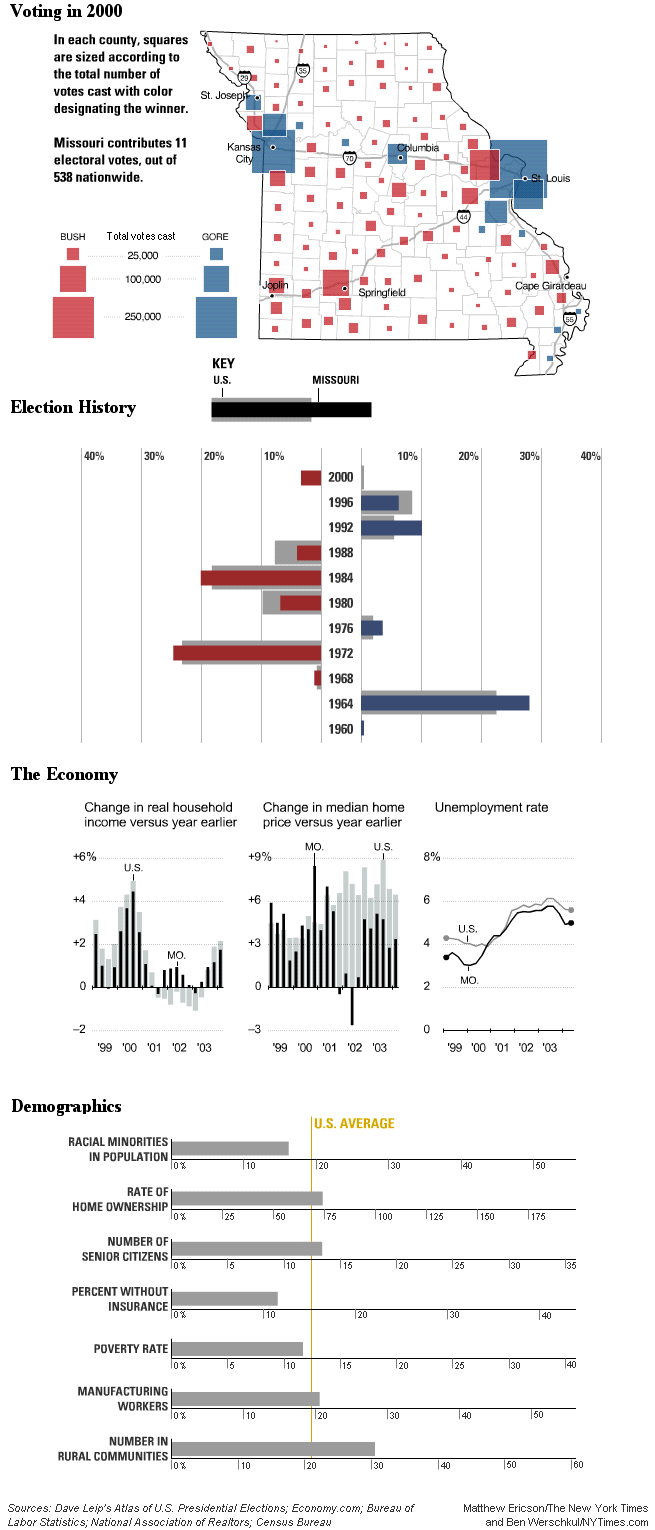

Missouri, almost evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, straddles the Midwest, the Deep South and the Great Plains, and has some of the sensibility of each region. Elections can turn on the interests of labor unions, farmers, city dwellers or suburban parents.

But Mr. Ampleman's internal tug of war, echoed in different ways in interviews with dozens of voters throughout the state, begins to explain why Republicans are increasingly confident they can prevail here this year, even as Democrats say they remain hopeful of winning Missouri's 11 electoral votes.

Residents from blighted city neighborhoods and gritty industrial outskirts to the leafy suburban enclaves and vast stretches of rolling hills and open farmland exude anxiety over the economy and the Iraq war that Senator John Kerry, the Democratic nominee, hopes to transform into votes. But they also echo the Christian-influenced social values and distaste for big government and taxes that helped propel President Bush to the White House. In August, a referendum on a proposed amendment to the State Constitution banning gay marriage was approved with 71 percent of the vote.

The cultural divisions run deep, even within families. Take Paula D. Hamilton, an African-American financial adviser who lives in Raytown, a middle-class suburb of Kansas City. Over the years she has swung between parties, and this time around she too is in a quandary.

She says she is impressed with Mr. Bush's strong stance on terrorism but unsure whether the country should have gone to war with Iraq. She finds Mr. Bush's emphasis on religion-based solutions to social problems appealing, but worries about jobs lost during his administration and what she calls an unfair tax burden on the middle class.

"I'm really thinking about who I'm going to vote for," Ms. Hamilton said, after hearing Vice President Dick Cheney speak at a rally in Springfield, some three hours' drive south of her home. "We need someone in our office who doesn't cower down," she continued. But, she added: "I'm looking at the numbers, at how many of our troops are being killed and tortured. I'm just concerned."

Ms. Hamilton said that she would probably not make up her mind until she walked into the voting booth. But her son, Zacqrey Woods, pastor at the Greater Metropolitan Baptist Church in Springfield - "the buckle of the Bible Belt," as he put it - has no such difficulties.

"I can't get past the moral issues, I just can't," said Mr. Woods. "So I cannot in any way support the Democratic Party," because of his objections to abortion and homosexuality.

Experts point to other factors that may come into play. "The gay marriage amendment reproduces what I think is the quiet cleavage in Missouri, which is urban-rural," said Dave Robertson, a political science professor at the University of Missouri at St. Louis. Gone are the days when candidates could carry the state by winning St. Louis and Kansas City, campaign strategists say. In both Democratic and Republican rural counties, where the gay marriage ban passed by much higher margins than in the cities and suburbs, "those traditional values are very strong," Professor Robertson said. And Republicans, who dominate the legislature, argue that Mr. Bush best reflects those values.

Even so, part of what has made politics in the state so fluid is that Missouri is such an amalgam. "We are a state of parts," said Gov. Bob Holden, a Democrat who grew up in the Bootheel, a cotton-growing area in the state's southeastern corner. "We touch as many states as any other state in the nation." Adding that the state frequently votes with the winning presidential candidate, he said, "If Al Gore could have carried Missouri in 2000, he would be president today, irrespective of what happened in Florida." (Mr. Gore lost by fewer than 80,000 votes.)

Boosters like to say that Missouri mirrors the country, with representative proportions of whites, blacks, union members, urban and rural residents and the elderly. More than half of the state's population of 5.7 million is concentrated in and around the Democratic strongholds of St. Louis and Kansas City, but the remaining landscape is largely small towns and rural areas.

Officials of both campaigns say the key to victory here lies in mobilizing core supporters and swaying a relatively small population of moderate, undecided voters, many in the counties ringing the large cities.

Toward that end, both campaigns have large ground operations in place and have been intensifying their presence of late. Mr. Bush has come to the state 21 times since his inauguration, visiting on 9 days this year, while Mr. Kerry has visited on 12 days since securing the nomination in March.

But there are signs that the tide may be shifting in Mr. Bush's direction. After months of running virtually even in opinion polls, Mr. Bush has taken a double-digit lead in at least one recent survey, from CNN/USA Today/Gallup. And although Mr. Kerry and his allies advertised more aggressively than the Bush campaign in the spring, that balance has now shifted as the Kerry camp has sharpened its focus on other battleground states.

Even so, strategists on both sides of the aisle say it is too early to count out Mr. Kerry, especially because the issues of most concern in the state, the economy and the war in Iraq, cut both ways.

Like many other states, Missouri has been bleeding manufacturing jobs. At the same time, the airline industry, which was strong here, has suffered since the Sept. 11 attacks. But there are signs that the economy is rebounding. Since July 2003, economic analysts say, the state has gained nearly 83,000 jobs, many in health services and tourism, bringing it closer to its pre-recession levels. Although the most recent figures show a net loss of 57,000 jobs for July and August, labor officials say most of that is in the educational sector and is likely to rebound in the fall.

Republicans like to cite their party's emphasis on tax cuts as a major factor in the state's economic growth, and they say their policies better dovetail with Missouri's libertarian spirit. But Democrats point to vanishing industries and an unemployment rate that has been creeping up. They say the task is to make sure that voters like Frank Brown, who works in an auto repair shop in Chaffee, a small town near conservative Cape Girardeau on the Mississippi, focus on their pocketbooks.

"You hate to see any small jobs go out, whether they've got two people or 200 people," said Mr. Brown, who said he tends to vote Democratic but had not yet made up his mind this year. "They want to tell these people, 'Well, we'll train you for something else.' Well, maybe they could have stopped that before that job went overseas."

Similarly, events in Iraq will play a role here in determining which lever is pulled by undecided voters like Jason Horn, who works as a portfolio manager in downtown St. Joseph, a livestock and manufacturing city an hour north of Kansas City.

"I guess if someone announces they're going to jack my taxes way up or something, sure, it could affect the way I vote," said Mr. Horn, who is in the National Guard and says he voted for Mr. Bush in 2000. But he added that the more important factors were foreign policy and military policy, including benefits for service members, as well as whether or not the country is at war, and where.

But in the end, many people may vote more on values and culture than on policy in a state that houses the headquarters of the Assemblies of God; where the Archbishop of St. Louis has said he would deny communion to Mr. Kerry, a Roman Catholic, because he supports abortion rights; and where hand-lettered signs for churches dot meandering country roadsides. Indeed, for some voters, like Stephanie Helfrich, a practicing Catholic who lives in the St. Charles area, values and policy are inextricably intertwined.

"Those values affect how you're going to make decisions on other things," Ms. Helfrich said, explaining that she planned to vote for Mr. Bush primarily because of his anti-abortion stance. "I would be suspect of someone making decisions about the war or the economy or whatever comes up without that strong foundation of the respect for life and the sanctity of marriage."

Kerry strategists hope that his military background and fondness for hunting will help him win votes in a state with a sizable veteran population and strong pro-gun sentiments (a state law allows residents to carry concealed weapons). Four years ago, rural and small-town voters went overwhelmingly for Mr. Bush, but the Kerry camp says it plans to deploy yet another weapon: his running mate, John Edwards, who has displayed a willingness to highlight his own small-town background.

Whether the tactics will work remains to be seen. Donnie Kiefer, a Democrat who runs the auto repair shop in Chaffee, said that his hometown was becoming more Republican because of "the pro-life and the pro-gun."

"You know, that's just a Republican political tool," he said. "They're going to stay with it and I don't blame them, because it's just smart on their part."